Chapter Twenty-two

The 1930s

Germany in Trouble

The

legend persists that Germany’s Weimar Republic fiddled while

Rome burned and that it collapsed because apathetic and hedonistic Germans were

unaware or indifferent to the dangers posed by the Nazis;

however, 71% of voters turned out for the July 1932 elections

in Germany, compared to, for example, 53% turnout in the

November 1932 American presidential election, so it obviously

wasn’t a lack of public participation that paved the way for

the Nazis. Newspapers like the Munich Post (the Poison

Kitchen, as Hitler called them) had been on the frontlines,

reporting every crime, scandal and outrage committed by the

Nazis throughout the 1920s despite violent Nazi retaliation.

The

legend persists that Germany’s Weimar Republic fiddled while

Rome burned and that it collapsed because apathetic and hedonistic Germans were

unaware or indifferent to the dangers posed by the Nazis;

however, 71% of voters turned out for the July 1932 elections

in Germany, compared to, for example, 53% turnout in the

November 1932 American presidential election, so it obviously

wasn’t a lack of public participation that paved the way for

the Nazis. Newspapers like the Munich Post (the Poison

Kitchen, as Hitler called them) had been on the frontlines,

reporting every crime, scandal and outrage committed by the

Nazis throughout the 1920s despite violent Nazi retaliation.

![like a big baby with a thin mustache penciled on [Stresemann]](images/1925Gustav_Stresemann.jpg) By 1924, the German

government had stabilized and survived most of its threats.

They stopped printing crates of fresh currency whenever they

needed more money. Germany became a member in good standing of

the League of Nations, and new agreements signed in 1924 and

1929 made reparation payments less painful. Much of the credit

for this recovery goes to Gustav

Stresemann, a good-natured facilitator with a broad,

jovial face. A member of the German People's Party (DVP), a

small party of free-market liberals that formed the right wing

of the Grand Coalition, Stresemann served briefly as

Chancellor, then continuously as Foreign Minister through

multiple cabinets, winning the Nobel Peace Prize for his

efforts in 1926. He died in October 1929 a few weeks before

the American stock market crashed and took civilization down

with it.Ⓐ

By 1924, the German

government had stabilized and survived most of its threats.

They stopped printing crates of fresh currency whenever they

needed more money. Germany became a member in good standing of

the League of Nations, and new agreements signed in 1924 and

1929 made reparation payments less painful. Much of the credit

for this recovery goes to Gustav

Stresemann, a good-natured facilitator with a broad,

jovial face. A member of the German People's Party (DVP), a

small party of free-market liberals that formed the right wing

of the Grand Coalition, Stresemann served briefly as

Chancellor, then continuously as Foreign Minister through

multiple cabinets, winning the Nobel Peace Prize for his

efforts in 1926. He died in October 1929 a few weeks before

the American stock market crashed and took civilization down

with it.Ⓐ

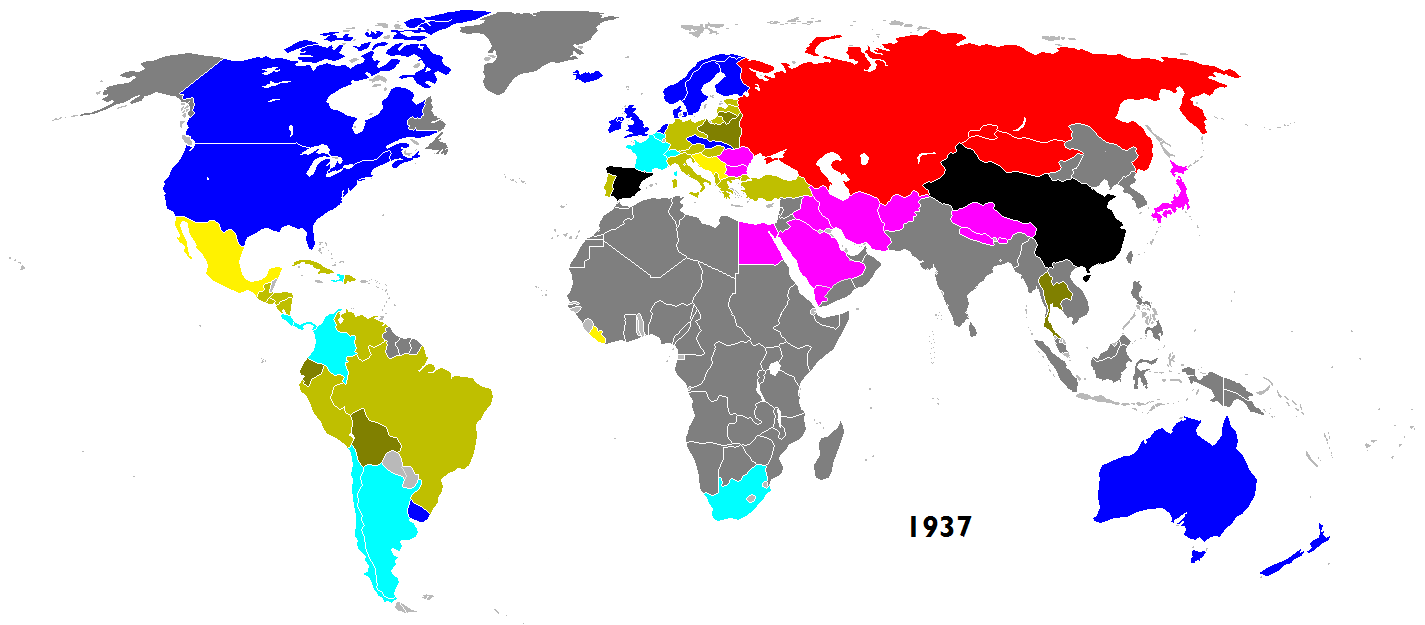

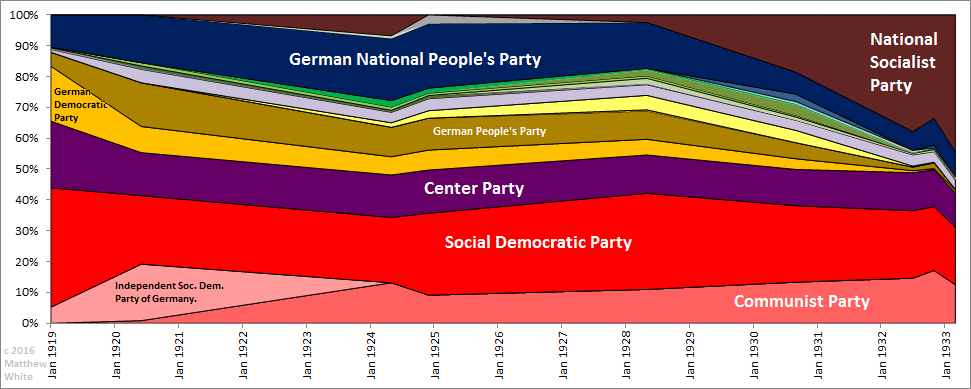

More than the Versailles Treaty and all that, it was the Great Depression that killed the Weimar Republic. By September 1930, three million Germans were out of work, a number that climbed to 5 million by 1932. At the peak of the Great Depression, one out of every three workers in Germany was unemployed. As the overwhelming reality of the worldwide economic collapse began to sink in, the voters became even more desperate for any kind of solution. Throughout the Twenties, the screaming hotheads of the far right with their banners, uniforms, paranoid scapegoating and pie-in-the-sky schemes to return to the Good Old Days had been the butt of jokes. So was their silly leader with the Charlie Chaplin mustache. Now the Nazi vision of a revitalized Germany cleansed of its enemies was starting to look pretty good to the hungry workers.

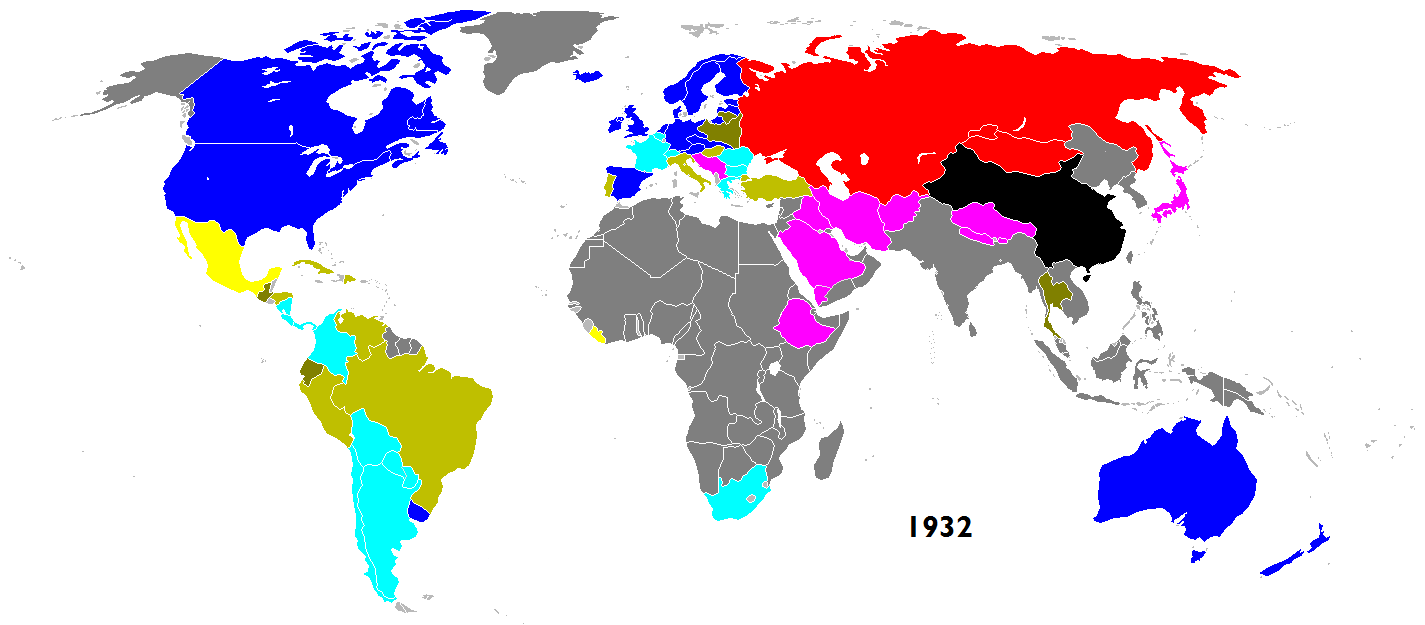

At first, Germany had been split evenly between left and right. In the December 1924 elections, 42% of the German electorate voted for right-wing parties and the same percentage voted for left-wing parties (defined here as right and left of the Center Party). Then the electorate shifted rightward. In the 1930 election, the right wing collected 50% of the vote, while only 37% of the vote went to the left-wing.

During the 1920s, the dominant party among extreme conservatives had been the German National People's Party (DNVP) under Alfred Hugenberg, a wealthy newspaper tycoon who used his media empire to promote the party line. Antidemocratic and strongly backed by business interests, DNVP got much of its rank-and-file voting strength from rural districts that didn’t trust modern urban society, and from older middle class voters who didn’t trust change.

In

the election of May 1928, before the Great Depression, the

Nazis had won only 3% of the vote, leaving them 9th in a

Reichstag dominated by the Social Democrats of the moderate

left who had 29%, or ten times the voting strength of the

Nazis; however, after the crash, the German right wing shifted

from the DNVP (half the right wing and 21% of the overall

vote) to the Nazis (40% of the right wing and 18% of the

overall vote in 1930). Now the Nazis were second to the Social

Democrats in the number of seats

in the Reichstag.

In

the election of May 1928, before the Great Depression, the

Nazis had won only 3% of the vote, leaving them 9th in a

Reichstag dominated by the Social Democrats of the moderate

left who had 29%, or ten times the voting strength of the

Nazis; however, after the crash, the German right wing shifted

from the DNVP (half the right wing and 21% of the overall

vote) to the Nazis (40% of the right wing and 18% of the

overall vote in 1930). Now the Nazis were second to the Social

Democrats in the number of seats

in the Reichstag.

The shabby hooligans of the Nazi Party worried the traditional German right wing. Hindenburg hated Adolf Hitler and talked about him as “that Bohemian corporal”, but with the Nazis gaining in popularity, something had to be done to bring them under control. In 1931, the German right wing met at the Nazi-controlled town of Harzberg where they joined into a coalition called the Harzberg Front. The non-Nazi right wing hoped that bringing Hitler into partnership with several of the more established parties would help control him, but instead, this granted the Nazis a cloak of legitimacy they hadn’t had before.

Throughout the Weimar era, politics was a soccer ball kicked around and head-butted by street-fighting paramilitaries. These uniformed bullies broke up rallies, beat up speakers, chased away voters and destroyed the presses of the opposition. No one could stop them because the army had been cut back to almost nothing by the Treaty of Versailles. The most infamous of them were the brown-shirted Nazi Stormtroopers (Sturmabteilung or SA). Brawling alongside them in a loose alliance was the Steel Helmet, technically a simple veterans’ society, but in reality the largest of all the paramilitaries with a half million members clubbing Commies on behalf of the ultraconservative DNVP. The Steel Helmet was pretty much the new face of the old Freikorps. On the other side was the Red Front Fighters' League, busting skulls for the Communists. Caught between the two extremes was the Reichsbanner Black-Red-Gold protecting the Social Democrats. Towards the end of the Weimar Era, the Reichsbanner and other centrist streetfighters coalesced into the Iron Front to defend sanity and face the Harzburg Front for one final battle.

Nazi Germany Arrives

As Hindenburg’s seven-year term as president was coming to an end, Germany’s leaders began jostling for a slot on the ballot. The Communists could be counted on to run Ernst Thälmann, their usual spoiler candidate who would syphon votes from the Social Democrats and keep the left wing from winning as a bloc. Hitler’s popularity was steadily rising. By mastering new technologies like radio and airplanes, he could take his paranoid but compelling message directly and personally to a wider audience. He now stood a good chance of capturing the right wing. Hindenburg was old and just wanted to nap, but German moderates were convinced he was the only one in Germany who could stop Hitler, so they begged him to run again. This time, instead of being the candidate of the far right, the electorate had shifted so far that both the Center Party and Social Democrats supported Hindenburg. Two rounds of voting in March and April 1932 ended with Hindenburg getting 53%, Hitler 37% and Thälmann 10%.

From

1930 to 1932, while Hitler was starting to be taken seriously,

the Chancellor of Germany was Heinrich Brüning of the Center

Party. The longest serving of any Weimar chancellor, he was

probably the last leader of Germany to believe in democracy.

Then one day in May 1932, Brüning suggested taking over some

bankrupt estates of impoverished Prussian nobility and

dividing the land among the peasants. Hindenburg, a Prussian

nobleman himself, was furious and fired him. With Brüning

gone, the fate of Germany now came down to which power-hungry

right-wing politician would end up in control – either Hitler

or someone else, hopefully not as bad as Hitler.

From

1930 to 1932, while Hitler was starting to be taken seriously,

the Chancellor of Germany was Heinrich Brüning of the Center

Party. The longest serving of any Weimar chancellor, he was

probably the last leader of Germany to believe in democracy.

Then one day in May 1932, Brüning suggested taking over some

bankrupt estates of impoverished Prussian nobility and

dividing the land among the peasants. Hindenburg, a Prussian

nobleman himself, was furious and fired him. With Brüning

gone, the fate of Germany now came down to which power-hungry

right-wing politician would end up in control – either Hitler

or someone else, hopefully not as bad as Hitler.

In the August 1932 election, the Nazis received 37% of the vote (13.7 million), more than anyone else. The Germans immediately suffered a collective panic attack once they realized what they had done, so Hindenburg arranged new elections in November 1932 to give everyone a chance to come to their senses. Two million Nazi voters now switched to someone else, so the Nazis only got 11.7 million votes, or 33%. Even though democratic support for the Nazi had topped out, they were still the largest party in parliament and hard to ignore.

For many months, the major power brokers of the German right wing tried their best not to put Hitler in charge. They tried to placate him with lesser positions while they elevated safer politicians to the top post. Franz von Papen of the Center Party was chancellor awhile, but when that didn’t work out, Hindenburg’s nonaffiliated advisor General Kurt von Schleicher was moved into the position. Hitler refused to cooperate with any of them, and with the Nazis being the largest party in the Reichstag, his intransigence deadlocked the German government. Nazi mobs launched strikes and rallies. They intimidated the opposition with vandalism, threats and beatings, hoping to encourage German leaders to accept their man as chancellor. Finally the businessmen and generals behind the right wing convinced Hindenburg that maybe it would calm the country down if he just gave Hitler a chance – after all, how bad could he be? - so Hindenburg held his nose and appointed him as chancellor in January 1933. Papen was assigned the job as Vice-Chancellor to keep an eye on Hitler and make sure he didn’t do anything crazy. New elections were scheduled for March in any case, so Hitler shouldn’t be in charge too long.

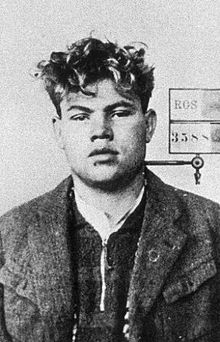

On

February 27, 1933, less than a month into Hitler’s term and

less than a week before the elections, a fire in the late

evening gutted the Reichstag Building. To this day, we don’t

entirely know who was behind it, but Marinus

van der Lubbe, a half-witted 24-year-old Dutch

Communist and unemployed bricklayer was found wandering

shirtless around the ruins. He happily confessed that he

wanted to strike a blow against the system without harming

people so he had set fire to the capitol at night all by

himself using his shirt as kindling. On the other hand, the

fire fit into the Nazis’ plans so neatly that it’s hard not to

suspect they had a hand in it.

On

February 27, 1933, less than a month into Hitler’s term and

less than a week before the elections, a fire in the late

evening gutted the Reichstag Building. To this day, we don’t

entirely know who was behind it, but Marinus

van der Lubbe, a half-witted 24-year-old Dutch

Communist and unemployed bricklayer was found wandering

shirtless around the ruins. He happily confessed that he

wanted to strike a blow against the system without harming

people so he had set fire to the capitol at night all by

himself using his shirt as kindling. On the other hand, the

fire fit into the Nazis’ plans so neatly that it’s hard not to

suspect they had a hand in it.

Hitler blamed the fire on a Communist conspiracy and insisted that President Hindenburg grant him emergency powers to crush the Communists. The president’s Reichstag Fire Decree temporarily gave Hitler the authority to ban the opposition press and arrest thousands of Communists without much fuss, most of whom would never see the outside world again. When the elections rolled around a few days later, everyone knew this would be their last chance -- for the Nazis, their last chance to take power, and for the left wing, their last chance to stop Hitler. The Nazis needed to win by a clear majority in order to lock up power for good. Right wing militias supported by all the resources of the state were unleashed on the opposition, but even after an outburst of arrests, beatings and murders gutted the left wing, the Nazis still took in only 44% of the vote. Hitler had to make nice with the DNVP in order to add their 8% to his voting bloc for a majority.

This gave

the Nazis enough power for ordinary government business, but

to shift absolute power to the Chancellorship, Hitler needed

two-thirds of the Reichstag to vote for it. Even with the

Communist Party outlawed, arrested and expelled from the

Reichtag, it proved difficult reducing the opposition to less

than one-third. A few more percentages in favor of Hitler

could be found with small ultranationalist parties, but the

only accessible big bloc of votes was the 11% held by Center

Party of the moderate right wing. By promising to leave the

Catholic Church alone, Hitler got their support. The Enabling

Act, which extended Hitler’s authority to rule by decree for

“four years” (i.e. forever), passed the Reichstag on March 25,

1933. Only 84 Social Democrats voted against it, and most of

them found it wise to leave the country soon afterwards.

Opponents who stayed in Germany quickly ended up in the brand

new concentration camp at Dachau. The Munich Post, Hitler’s

most passionate critic throughout his career, was ransacked

and shut down; its reporters were jailed, often for the rest

of their lives. Hitler’s power was secure.

This gave

the Nazis enough power for ordinary government business, but

to shift absolute power to the Chancellorship, Hitler needed

two-thirds of the Reichstag to vote for it. Even with the

Communist Party outlawed, arrested and expelled from the

Reichtag, it proved difficult reducing the opposition to less

than one-third. A few more percentages in favor of Hitler

could be found with small ultranationalist parties, but the

only accessible big bloc of votes was the 11% held by Center

Party of the moderate right wing. By promising to leave the

Catholic Church alone, Hitler got their support. The Enabling

Act, which extended Hitler’s authority to rule by decree for

“four years” (i.e. forever), passed the Reichstag on March 25,

1933. Only 84 Social Democrats voted against it, and most of

them found it wise to leave the country soon afterwards.

Opponents who stayed in Germany quickly ended up in the brand

new concentration camp at Dachau. The Munich Post, Hitler’s

most passionate critic throughout his career, was ransacked

and shut down; its reporters were jailed, often for the rest

of their lives. Hitler’s power was secure.

But first there was a bit of tidying up. The Nazis had two paramilitaries, the Stormtroopers (SA), the brown-shirted bullies for intimidating the opposition, and the Protection Squad (Schutzstaffel: SS), Hitler personal bodyguard. The SA were uncompromising ideological bruisers and loose cannons. They had been useful in the street fighting days, but now that the Nazis were in charge, Hitler decided that leaving unattended ideologues wandering around was too dangerous. The army didn’t trust them either.

The SS was personally loyal

to Hitler, so on the Night of the Long Knives, June 30, 1934

he sent the SS to kill the leaders of the SA and disarm

the rank and file. This was also a perfect

opportunity to remove former rivals and allies in the right

wing who were starting to have second thoughts about putting

Hitler in charge. Former Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher and

his wife were murdered, as were many associates of

Vice-Chancellor Franz von Papen who had tried to keep Hitler

sidelined. Papen was too visible to kill, but he kept quiet

after this. Hitler spread the excuse that he had snuffed out

an impending coup in the nick of time. Hindenburg, barely

alive at this point, thanked him for his diligence and died of

lung cancer in August, removing the last German who wasn’t

Hitler from power.

perfect

opportunity to remove former rivals and allies in the right

wing who were starting to have second thoughts about putting

Hitler in charge. Former Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher and

his wife were murdered, as were many associates of

Vice-Chancellor Franz von Papen who had tried to keep Hitler

sidelined. Papen was too visible to kill, but he kept quiet

after this. Hitler spread the excuse that he had snuffed out

an impending coup in the nick of time. Hindenburg, barely

alive at this point, thanked him for his diligence and died of

lung cancer in August, removing the last German who wasn’t

Hitler from power.

You can never be sure how history might have turned out with just a few little changes here and there, but the popular consensus seems to be that even if Hitler hadn’t been there, someone would have filled the gap and done the same things he did - the mood of Germany would see to it - however, let’s not forget that it would have been very difficult for Germany to come up with someone else as bad as Hitler. In many ways, the rise of Hitler was unlikely. If Ebert hadn’t died… If Stresemann hadn’t died… If someone had deported Hitler back to Austria as they were legally allowed… If the Communists had cooperated with the Socialists in a Popular Front as they later did in France and Spain… If the DNVP had remained the dominant voice of the extreme right wing… if the army had cracked down on the paramilitaries… if parliament hadn’t panicked after the Reichstag fire… if the Center Party didn’t cave in…

The world just had a run of really bad luck is what I’m saying.

Fall of Democracy in Europe

Although tradition has blamed the collapse of the Weimar Republic on the harsh terms the Versailles Treaty imposed on a defeated Germany, the problems were not unique to Germany. Democracies failed all across Europe during the Great Depression regardless of their experience in the First World War. As the global economy sputtered to a halt and voters became desperate, the lure of fascism dragged most countries to the right. Many only escaped the worst when moderate right-wing politicians took dictatorial control and banned the extremists. Despite the widespread fear that the greatest danger to democracy came from unemployed workers on the far left, Communists didn’t even come close to taking over any European governments during the Great Depression.

In Estonia, Konstantin

Päts, of the moderate right-wing party, the Farmers’

Assemblies, had pretty much run the country since

independence. He had been leader of the provisional

government, and once the permanent constitution took effect,

he continued to be prime minister off and on depending on the

mood of the voters. Even when his party lost a round of

elections, it usually won enough seats in parliament to get a

few slots in a coalition government. In 1932, an extreme

right-wing veterans’ league (the Vaps Movement) pushed through

a new constitution creating a strong presidency, which they

were hoping to win in the next election. Of course, Konstantin

Pats won instead. Frustrated and angry, the Vaps tried a

couple of failed coups against President Pats, so he outlawed

them and declared a state of emergency. In January 1934, he

disbanded parliament and ruled by decree for the next few

years, until Estonia was swallowed by the Soviet Union in

1940.

In Estonia, Konstantin

Päts, of the moderate right-wing party, the Farmers’

Assemblies, had pretty much run the country since

independence. He had been leader of the provisional

government, and once the permanent constitution took effect,

he continued to be prime minister off and on depending on the

mood of the voters. Even when his party lost a round of

elections, it usually won enough seats in parliament to get a

few slots in a coalition government. In 1932, an extreme

right-wing veterans’ league (the Vaps Movement) pushed through

a new constitution creating a strong presidency, which they

were hoping to win in the next election. Of course, Konstantin

Pats won instead. Frustrated and angry, the Vaps tried a

couple of failed coups against President Pats, so he outlawed

them and declared a state of emergency. In January 1934, he

disbanded parliament and ruled by decree for the next few

years, until Estonia was swallowed by the Soviet Union in

1940.

Almost the exact same

thing happened in Latvia: Kārlis Ulmanis of the

right-wing Latvian Farmers' Union was the first prime minister

after independence from Russia. For the next 14 years, he

moved in and out of the office depending on how the latest

votes went. Finally the Great Depression brought out the

crazies, and Ulmanis assumed dictatorial powers (1934) to keep

power out of the hands of right wing militias. In 1940, Russia

reconquered the country.

Almost the exact same

thing happened in Latvia: Kārlis Ulmanis of the

right-wing Latvian Farmers' Union was the first prime minister

after independence from Russia. For the next 14 years, he

moved in and out of the office depending on how the latest

votes went. Finally the Great Depression brought out the

crazies, and Ulmanis assumed dictatorial powers (1934) to keep

power out of the hands of right wing militias. In 1940, Russia

reconquered the country.

In Finland, under

pressure from the far right, the government stripped 20,000

suspected communists of the right to vote before the 1930

elections in Finland. This resulted in a right wing victory

that allowed them to permanently outlaw the Communist party.

For the rest of the decade, democracy remained, but elections

usually veered rightward. The nation’s leadership was passed

around among the top conservative parties.

In Finland, under

pressure from the far right, the government stripped 20,000

suspected communists of the right to vote before the 1930

elections in Finland. This resulted in a right wing victory

that allowed them to permanently outlaw the Communist party.

For the rest of the decade, democracy remained, but elections

usually veered rightward. The nation’s leadership was passed

around among the top conservative parties.

In 1932, the upcoming election

in Austria was threatening to replace the conservative

parliamentary majority of Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss with

leftists, so Dollfuss bypassed parliament and began ruling by

decree using the emergency powers that Austria’s constitution

allowed during wartime, despite the rather obvious objection

that there was no war at the time. Dollfuss outlawed parties

of the extreme left and right, and when a meeting of

socialists fought back against a police raid looking for

troublemakers, he outlawed the moderate left as well. In 1934,

Austrian Nazis assassinated Dollfuss as the first stage of a

coup d’etat, but this uprising was crushed. Another local

dictator took control, so Austria avoided being absorbed into

Germany for another few years.

In 1932, the upcoming election

in Austria was threatening to replace the conservative

parliamentary majority of Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss with

leftists, so Dollfuss bypassed parliament and began ruling by

decree using the emergency powers that Austria’s constitution

allowed during wartime, despite the rather obvious objection

that there was no war at the time. Dollfuss outlawed parties

of the extreme left and right, and when a meeting of

socialists fought back against a police raid looking for

troublemakers, he outlawed the moderate left as well. In 1934,

Austrian Nazis assassinated Dollfuss as the first stage of a

coup d’etat, but this uprising was crushed. Another local

dictator took control, so Austria avoided being absorbed into

Germany for another few years.

Greek democracy was

already pretty shaky but it briefly restabilized from 1928 to

1932 under the same experienced but intermittent prime

minister we’ve met before, Eleftherios Venizelos. Then the

Great Depression knocked it off balance again. With the

economy a wreck, people began to grumble that maybe Greece

needed the strong hand of a king again. The army stepped in to

take control in October 1935 and held a plebiscite in November

to decide this once and for all. Each voter was given a blue

ball and a red ball. There was no private voting, so at each

polling place, the vote was cast under the eyes of watchful

neighbors. The voter would drop a blue ball into the ballot

box if they wanted to restore the monarchy and a red ball if

they wanted to get beaten up by monarchists for voting against

the monarchy. Under those circumstances, 98% of the voters

decided that yes, they wanted a king again. Even then, Greece

continued to crumble into ruin, so on 4th August 1936,

Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas gave himself the authority to

rule by decree. The king approved and that was that.

Greek democracy was

already pretty shaky but it briefly restabilized from 1928 to

1932 under the same experienced but intermittent prime

minister we’ve met before, Eleftherios Venizelos. Then the

Great Depression knocked it off balance again. With the

economy a wreck, people began to grumble that maybe Greece

needed the strong hand of a king again. The army stepped in to

take control in October 1935 and held a plebiscite in November

to decide this once and for all. Each voter was given a blue

ball and a red ball. There was no private voting, so at each

polling place, the vote was cast under the eyes of watchful

neighbors. The voter would drop a blue ball into the ballot

box if they wanted to restore the monarchy and a red ball if

they wanted to get beaten up by monarchists for voting against

the monarchy. Under those circumstances, 98% of the voters

decided that yes, they wanted a king again. Even then, Greece

continued to crumble into ruin, so on 4th August 1936,

Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas gave himself the authority to

rule by decree. The king approved and that was that.

The micronations of Europe were hit by the crisis as well. The local fascists started winning elections in the independent Italian city-state of San Marino in 1923, and by 1926 all other parties were banned. Nazis won the 1933 elections in the Free City of Danzig (now Gdansk on the Polish coast), and within a couple of years, they had banned opposition parties. The only reason Danzig remained a free city rather than a German province was that it was ultimately under the jurisdiction of the League of Nations, and Germany wasn’t going to start a war against the whole world quite yet.

Several constitutional monarchies of East Europe which had been puttering along as sleepy anocracies (hybrid regimes) also fell under the spell of homegrown fascist organizations. A 1934 coup d’état in Bulgaria replaced the ruling bourgeois oligarchy with the fascist Link Movement. The Hungarian dictator Miklós Horthy had to start cooperating with the fascist Arrow Cross during the mid-1930s. King Carol II of Romania tried holding off the Romanian fascists of the Iron Guard by seizing dictatorial control from his parliament in 1938, but he was outmaneuvered and deposed by the fascists in 1940.① These three lesser fascist countries would become allies of Germany during the upcoming world war, and afterward they fell to Soviet retaliation.Ⓓ

|

|

Latin America too

The Great Depression also discredited and undermined democracy in Latin America as well as Europe. Many turned decidedly authoritarian around 1930.

In Argentina the era became known as the Infamous Decade, which began and ended with military coups in 1930 and 1943 respectively. Although the forms of democracy were in place between these bookends and citizens were free to argue with each other all they wanted, all the major elections were corrupt and the threat of another coup constantly hung over the country. Across the water from Buenos Aires, Uruguay was having its own troubles too. Theirs was usually the most democratic government in its neighborhood, and Uruguayans tried to hold on, but as the economy worsened, President Terra consolidated all power into his own hands and settled into a dictatorship between 1933 and 1942.

In the run-up to the Spanish-American War, the US had made such a big deal about Cuban independence that they couldn’t just annex the island outright, but they wrote the treaties to give themselves the right to step in if the Cubans did anything the US didn’t like. Aside from that, Cuba was sort of democratic from 1908 until 1930, when the military stepped in to run the place during the Great Depression. Democracy of a sort returned from 1940 to 1952.

Brazil had been an oligarchy of landowners and industrialists under its First Republic from 1889 to 1930, but the onset of economic bad times sparked a military uprising that installed Getúlio Vargas as dictator with many of the trappings of a fascist state.

Japan

After World War One,

Japan started to show some characteristics of a real

democratic government. The mental and physical health of the

new young Taisho Emperor (ruled 1912-26) started out bad and

deteriorated quickly, so political power devolved onto

parliament while he withdrew from public life. As the

Japanese got more experience with the give and take of

politics, they developed two parties replicating the

left/right split found in other legislatures. In 1918 Hara

Takashi became the first commoner selected as prime minister,

but in 1921, after trying to bring a measure of self-rule and

cultural tolerance to Japan’s colony of Korea, Hara was

assassinated by an angry ultra-nationalist railroad worker in

Tokyo Station.

After World War One,

Japan started to show some characteristics of a real

democratic government. The mental and physical health of the

new young Taisho Emperor (ruled 1912-26) started out bad and

deteriorated quickly, so political power devolved onto

parliament while he withdrew from public life. As the

Japanese got more experience with the give and take of

politics, they developed two parties replicating the

left/right split found in other legislatures. In 1918 Hara

Takashi became the first commoner selected as prime minister,

but in 1921, after trying to bring a measure of self-rule and

cultural tolerance to Japan’s colony of Korea, Hara was

assassinated by an angry ultra-nationalist railroad worker in

Tokyo Station.

To calm the country down, the two parties agreed to alternate in control of government for the next few years. Then the General Election Law of 1925 gave the vote to all men over 25 and the parties resumed competition.

Even though the monarchy wasn’t pushing back against this emerging Japanese democracy, the military was. They had big plans for assembling an Asia-Pacific empire, and no one was going to stop them. Under the constitution, the military answered only to the emperor and they got to pick their own defense minister, so there was no civilian check on their ambitions. Any civilian who meddled in their affairs was asking for a bullet.

For example, Prime Minister Hamaguchi Osachi of

the liberal Constitutional Democratic Party questioned a naval

treaty, and - in what was rapidly becoming a Japanese

tradition - he too was shot in Tokyo Station by an angry

ultranationalist in November 1929.③

He lingered with his wounds for several months and finally

died. The bodies began to pile up quickly after this.

Members of the secret paramilitary League of Blood

gunned down a  couple of prominent

internationalists who were trying to get Japan to abide by

international law: Finance Minister Inoue Junnosuke in

February 1932 and Dan Takuma, Director of the Mitsui Company,

in March 1932. A related conspiracy of young Japanese naval

officers, many still in their teens, planned to strike a blow

against decadent modern culture by killing Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi, but then,

a new target of opportunity presented itself when they learned

that Charlie Chaplin

would arrive on May 14, 1932 for a VIP tour of Japan.

couple of prominent

internationalists who were trying to get Japan to abide by

international law: Finance Minister Inoue Junnosuke in

February 1932 and Dan Takuma, Director of the Mitsui Company,

in March 1932. A related conspiracy of young Japanese naval

officers, many still in their teens, planned to strike a blow

against decadent modern culture by killing Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi, but then,

a new target of opportunity presented itself when they learned

that Charlie Chaplin

would arrive on May 14, 1932 for a VIP tour of Japan.

![Uncanny resemblance [The Great Dictator]](images/1940-The_Great_Dictator.jpg) As one assassin

explained at his trial: “Chaplin is a popular figure in the

United States and the darling of the capitalist class. We

believed that killing him would cause a war with America, and

thus we could kill two birds with a single stone.”Ⓑ

As one assassin

explained at his trial: “Chaplin is a popular figure in the

United States and the darling of the capitalist class. We

believed that killing him would cause a war with America, and

thus we could kill two birds with a single stone.”Ⓑ

As it turned out, they had to make do with killing only one bird. Instead of attending the May 15, 1932 reception at the Prime Minister's residence, Chaplin went to a sumo wrestling match with the prime minister’s son, so he wasn’t at the party when the eleven young officers attacked. Inukai's last words as he was struck down were “If we would speak, we would understand” to which his killers replied “No more discussion”.

The assassins were slapped on the wrist by a sympathetic court. Meanwhile in order to forestall an outright military coup by the most radical factions, Emperor Hirohito bypassed the political parties altogether and appointed a moderate military officer as replacement prime minister. From this point on, the prime minister was always a soldier, and the military would run Japan without interference. Although there were still a few assassinations and attempted coups yet in store, these were mostly power struggles among factions in the military. In the summer 1940, the major political parties were dissolved and bundled into the local fascist organization, the Imperial Rule Assistance Association, ending all pretense of democracy.

Colonies

By the 1930s, a consensus was forming in the West that imperialism was impractical, unprofitable and just plain immoral. More and more national leaders were coming to accept that all the people of the world deserved self-rule, especially in those colonies that already had centuries of literacy and global commerce behind them. In 1932, Britain gave Iraq a king and its independence. In 1936, the British agreed to withdraw most troops from the kingdom of Egypt.

Ever since Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887, Britain had been regularly summoning the leaders of the Empire’s settler colonies to England for non-binding discussions of global policy. The 1926 Imperial Conference was the seventh such meeting of leaders from all the white lands in the Empire – Australia, Canada, Ireland, Newfoundland, New Zealand, South Africa and the UK – plus India in a non-voting capacity. This meeting agreed that it was time for the Dominions to sit at the grownups’ table.

This new world

order was nailed down legally with the 1931 Statute of

Westminster, which reorganized the Empire into a Commonwealth

that granted immediate sovereignty to the dominions of Canada, Ireland and South

Africa, and started the process for Australia, Newfoundland

and New Zealand. The British King would remain as head of

state, but the British parliament would no longer legislate

for these countries.②

This new world

order was nailed down legally with the 1931 Statute of

Westminster, which reorganized the Empire into a Commonwealth

that granted immediate sovereignty to the dominions of Canada, Ireland and South

Africa, and started the process for Australia, Newfoundland

and New Zealand. The British King would remain as head of

state, but the British parliament would no longer legislate

for these countries.②

Left

out of the Commonwealth reorganization was India,

which the British were determined to keep

Left

out of the Commonwealth reorganization was India,

which the British were determined to keep and exploit. After the

failed Sepoy Rebellion of 1857 had drenched the land in blood,

the Indian independence movement had decided to become patient

and polite instead. Nationalist leaders encouraged everyone to

cooperate with the British, learn their ways and earn their

friendship. Then in 1919, imperial Indian troops under British

command cornered a large gathering of Indian protesters in the

courtyard of a temple in Amritsar.

and exploit. After the

failed Sepoy Rebellion of 1857 had drenched the land in blood,

the Indian independence movement had decided to become patient

and polite instead. Nationalist leaders encouraged everyone to

cooperate with the British, learn their ways and earn their

friendship. Then in 1919, imperial Indian troops under British

command cornered a large gathering of Indian protesters in the

courtyard of a temple in Amritsar.

Among other festering sore points, the British had given India an extra vigorous shakedown to help pay for the First World War. Protests erupted all over India, and the city of Amritsar had already seen outbreaks of violence, including the near-fatal assault of an English lady by a native mob. Believing that only a brutal show of force would teach these savages to respect authority, Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer threatened merciless retaliation against any Indians he spotted in the streets of Amritsar. After two days of lying low, the Indians then attempted a little light protesting again. Making good on his promise, Dyer deployed his troops and slaughtered the unarmed crowd with relentless rifle and machine gun fire. Trapped by the temple courtyard walls, the protesters couldn’t run away, and anywhere from three hundred to a thousand were killed. Although many British were horrified when the news of the massacre arrived in England, Dyer escaped any real punishment and he earned praise from the people in charge; however, the Amritsar Massacre convinced the new generation of India’s leaders to get out of the Empire sooner rather than later.

Leadership had started to focus on a couple of young Indians who had earned law degrees in England and then come home to practice -- Jarwahal Nehru and Mohandas Gandhi. Gandhi had started practicing law in South Africa where he organized the Indian immigrant workers, but by the time of Amritsar, he had returned home to India. By 1920 he had come to dominate the independence movement.

Mohandas Gandhi tended toward the spiritual rather than the political. In fact, he was so far beyond politics that he had some strangely original (or insanely naïve) notions instead of the usual political platitudes. He said that the Jews should have committed mass suicide in defiance of Hitler. When Indian Muslims under Jinnah demanded their own country, Gandhi suggested allowing them to rule over the all the Hindus rather than split India. That said, Gandhi was a master strategist who planned grand gestures to unite and excite the people. He always held the moral high ground, and there was no way to outfox Gandhi.

Gandhi’s flashiest move was the Salt March. The

British maintained a lucrative monopoly on salt. Indians were

not allowed to produce or sell salt. They had to buy it from

heavily taxed middlemen. ![1939: Mahatma Gandhi, centre, waits for a car outside Birla House, Bombay, with Jawaharlal Nehru, left [waitng for a bus]](images/1939GandhiNehru.jpg) In

defiance, Gandhi started walking to the sea in March 1930,

stopping at a new village every night to call on the people to

peacefully defy the British. His crowd of followers grew. He

finally arrived at the shore to dry seawater to extract salt.

As more Indians followed his example, the British became jumpy

and began making arrests. Soon the jails were filled to

capacity. Then just before Gandhi was to lead a protest march

to a major saltworks, the British arrested him too. This

outraged the Indian people, and mobs of them converged on the

saltworks to peacefully protest. The British authorities waded

into the crowd to beat some sense into them, but to no avail.

Gandhi was finally released in January 1931, and the British

started negotiating.

In

defiance, Gandhi started walking to the sea in March 1930,

stopping at a new village every night to call on the people to

peacefully defy the British. His crowd of followers grew. He

finally arrived at the shore to dry seawater to extract salt.

As more Indians followed his example, the British became jumpy

and began making arrests. Soon the jails were filled to

capacity. Then just before Gandhi was to lead a protest march

to a major saltworks, the British arrested him too. This

outraged the Indian people, and mobs of them converged on the

saltworks to peacefully protest. The British authorities waded

into the crowd to beat some sense into them, but to no avail.

Gandhi was finally released in January 1931, and the British

started negotiating.

The United States was letting go as well. In 1907, the Americans organized a territorial government for the Philippines in which Washington appointed the upper house of the legislature (the Philippine Commission) and governor, while the Filipino people elected the lower house (the Philippine Assembly). Every year afterwards, the Assembly formally requested the United States to please set them free, and every year, Congress pretended they couldn’t hear them. Finally, Washington gave in to their nagging and passed the Tydings-McDuffe Act in 1934. This set up an autonomous Commonwealth of the Philippines with its own President and full Congress elected by the people. The commonwealth had full control over everything except foreign policy. The act also started a ten-year countdown to outright independence.

The French were a few steps behind the English-speaking world in letting go of their colonies. They divided their colonial populations legally into French citizens (with full civil rights) and natives (with none), and the only way the latter could become the former was by speaking and writing fluent French, earning a good living and showing solid moral character. None of that was easy. With the exception of a few older settlements with special privileges, only 2,500 people of African ancestry out of the 8 million residents of French West Africa had assimilated enough to count as citizens.

The French had traditionally been tough colonial masters, and they were still putting down scattered revolts by natives in Ubangi-Shari (1927-31) and Indochina (1930-31). The local authorities on the ground in Africa, Guiana, and Indochina refused to ease up on the natives, even if Paris asked them to -- and Paris didn’t ask very often because Paris didn’t care. Then in May 1936, the Popular Front was elected in France. Leon Blum became the nation’s first socialist premier. French plans for their colonies now began to slowly turn towards more self-government and possible future independence. Natives who accepted French culture were given an easier path to citizenship. France legalized trade unions in the colonies in 1937, but even that was a halfway measure; only the educated and fluent in French were allowed to join.Ⓔ

While the older democracies were cutting their colonies lose, several younger countries had missed the 19th Century frenzy of conquest and now decided to catch up; however, timing is everything. It was not considered appropriate for them to begin a new round of empire-building now that the civilized world was turning away from that sort of thing, so when Japan invaded Manchuria (1931) and Italy invaded Abyssinia (1935), the rest of the world loudly (but impotently) condemned them. These countries also began greedily eyeing the older, more established colonies of other nations. Then Germany started to assemble a new empire out of its smaller European neighbors (Austria, Czechoslovakia: 1938) and the future looked especially worrisome.

![Map of Europe 1937 [Map of Europe 1937]](images/1937euro.gif)

Rear Guard of Democracy

Popular Fronts

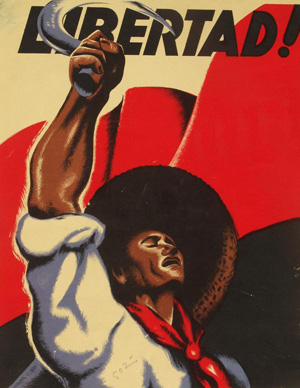

![Democracy breaking her chains, by David Alfaro Siqueiros, 1934 [Social realism]](images/1934_view-of-a-mural-depicting-democracy-breaking-her-chains-detail-of-the-series-new-democracy.jpg) In

1919 after the Russian Revolution, the Third International,

commonly called Comintern, was organized to spread communism

worldwide. Officially a global congress of national communist

parties that met every few years to coordinate strategy and

policy, it operated mostly as a tool of the Soviet foreign

policy and correlated pretty closely with events in the Soviet

Union. It was revolutionary under Lenin, idealistic under

Trotsky and paranoid under Stalin. The last global meeting of

Comintern – the Seventh Congress – took place in 1935, after

the split between Trotsky and Stalin had broken the unity of

world communism. In fact, Stalin was so suspicious of anything

calling itself “international” that at least 133 out of 492

Comintern staff members would later fall victim to Stalin’s

Great Purge, despite the rather obvious fact that these were

among the most dedicated communists in the world. Comintern

wasn’t officially dissolved until 1943, but by then it had

long ceased to be anything other than a branch of the Soviet

secret police enforcing Stalinist purity.

In

1919 after the Russian Revolution, the Third International,

commonly called Comintern, was organized to spread communism

worldwide. Officially a global congress of national communist

parties that met every few years to coordinate strategy and

policy, it operated mostly as a tool of the Soviet foreign

policy and correlated pretty closely with events in the Soviet

Union. It was revolutionary under Lenin, idealistic under

Trotsky and paranoid under Stalin. The last global meeting of

Comintern – the Seventh Congress – took place in 1935, after

the split between Trotsky and Stalin had broken the unity of

world communism. In fact, Stalin was so suspicious of anything

calling itself “international” that at least 133 out of 492

Comintern staff members would later fall victim to Stalin’s

Great Purge, despite the rather obvious fact that these were

among the most dedicated communists in the world. Comintern

wasn’t officially dissolved until 1943, but by then it had

long ceased to be anything other than a branch of the Soviet

secret police enforcing Stalinist purity.

The only reason to bring this up in a history of democracy is because the Seventh Congress of Comintern changed the rules for Communists in the West. Until 1935, Comintern had been instructing Communist parties to keep away from the dirty dealings of capitalists, to stay pure and not cooperate with outsiders. Their long-term goal was to watch passively while capitalism destroyed itself and then to move in to rebuild civilization along Marxist lines. We’ve already seen how well that worked in stopping Hitler. By 1935, the ongoing split in the Left Wing had let the fascists take over most of Europe without a fight, so finally Comintern turned around and instructed the communist parties in the last few democracies to make friends with the socialists and make fighting fascism their top priority. As a result, Popular Fronts created broad coalitions of leftists, ranging from hot-blooded banner-waving Communists to tweedy academic liberals, from open-minded urbanites to grimy factory-workers and tenant farmers. Popular Fronts were elected in France (1936), Spain (1936) and Chile (1937), stabilizing 2/3 of these wavering governments. The failure was Spain.

Spain

The Great Depression

undermined support for the status quo everywhere. In

Spain, dissatisfaction with the dictator Primo de Rivera

finally got loud enough for the king and the army to stop

supporting him. In 1930, Primo de Rivera resigned rather than

wait to be ousted. Republican candidates decisively won the

next round of elections, and the new parliament quickly

declared Spain to be a republic. King Alfonso XIII grumbled,

took the hint and left Spain, but he refused to accept their

decision and never formally abdicated.

The Great Depression

undermined support for the status quo everywhere. In

Spain, dissatisfaction with the dictator Primo de Rivera

finally got loud enough for the king and the army to stop

supporting him. In 1930, Primo de Rivera resigned rather than

wait to be ousted. Republican candidates decisively won the

next round of elections, and the new parliament quickly

declared Spain to be a republic. King Alfonso XIII grumbled,

took the hint and left Spain, but he refused to accept their

decision and never formally abdicated.

Spain was becoming dangerously unstable, and during the next election, the voters went wildly in the other direction. The right-wing coalition CEDA won the elections in November 1933, spurring leftist miners in Asturias to go on strike and seize their mines in opposition. The government sent colonial troops under General Francisco Franco to put down the uprising, killing 1,700 miners in the crackdown. In the backlash against the massacres, the left-wing Popular Front won the next round of elections in 1936 and started enacting a comprehensive leftist agenda.

Political violence was

increasingly common in Spain, and the nation’s security forces

were being pulled in opposite directions. The Civil Guard

(national military police) tended to be right wing, while the

Assault Guard (urban police force) leaned left. In July 1936,

Lieutenant José Castillo of the Assault Guard was shot down on

the street by Falangists (Spanish fascists), so the police

retaliated by arresting the right-wing political leader José

Calvo Sotelo, whom they shot and dumped at the gates of a

cemetery. The army got fed up with the whole mess, and the

Morocco garrison rose up under General Francisco Franco. Soon

military uprisings were everywhere, taking control of

strategic centers and summarily executing thousands of

leftists who fell into their hands.

Political violence was

increasingly common in Spain, and the nation’s security forces

were being pulled in opposite directions. The Civil Guard

(national military police) tended to be right wing, while the

Assault Guard (urban police force) leaned left. In July 1936,

Lieutenant José Castillo of the Assault Guard was shot down on

the street by Falangists (Spanish fascists), so the police

retaliated by arresting the right-wing political leader José

Calvo Sotelo, whom they shot and dumped at the gates of a

cemetery. The army got fed up with the whole mess, and the

Morocco garrison rose up under General Francisco Franco. Soon

military uprisings were everywhere, taking control of

strategic centers and summarily executing thousands of

leftists who fell into their hands.

![Five militiawomen of the Steel Battalion in the outposts of the first line of the front [Milicianas]](images/1936-milicianas.jpg) With the army against

them, the Republican government had to quickly improvise

militias to fight them off. Since the labor unions and the

Communists had the most well organized and toughest paramilitaries,

they came to form the backbone of the government’s army. This

shifted the Popular Front even farther leftward than they had

begun. The Republican armies retaliated against fascist

atrocities with atrocities of their own.

With the army against

them, the Republican government had to quickly improvise

militias to fight them off. Since the labor unions and the

Communists had the most well organized and toughest paramilitaries,

they came to form the backbone of the government’s army. This

shifted the Popular Front even farther leftward than they had

begun. The Republican armies retaliated against fascist

atrocities with atrocities of their own.

The Spanish Civil War became the dress rehearsal for World War Two. German and Italian troops arrived to support Franco’s Nationalist forces. Stalin sent military advisors to help prop up the Republican government. Foreign communist parties organized idealistic volunteers from all over the world – George Orwell and Ernest Hemingway most famously -- into the International Brigades to defend the democratic government of Spain.

Over the next three years of war, Franco’s Nationalists slowly but inexorably crushed the Republican resistance. As they took back Spain, they exacted a bloody revenge and executed countless supporters of the Popular Front. Tens of thousands of Republicans were shot or hanged after the war ended in 1939, perhaps even a hundred thousand or more. Franco then set up a repressive Fascist Regime to keep everyone under control.

|

|

Czechoslovakia

By the time the European crisis finally exploded, Czechoslovakia was the last lonely democracy left east of the Rhine and south of the Baltic.

The border

between Czechoslovakia and Germany followed the traditional,

geographically sensible border of Bohemia, which ran along the

crest of the Sudeten Mountains; however, most inhabitants of

the Sudeten Mountains on either side of the border were

Germans. The Czech majority of the country lived in the

Bohemian lowlands. This had not been a problem for the Sudeten

Germans when Bohemia was part of the Austrian Empire. They had

been among the privileged Germans who ran the empire, but now

they were an ethnic minority in a Slavic land. In practice,

the Czech government treated them quite well, just like they

treated anybody else. German was one of several official

languages across the republic, and most districts had a wide

degree of local autonomy.

The border

between Czechoslovakia and Germany followed the traditional,

geographically sensible border of Bohemia, which ran along the

crest of the Sudeten Mountains; however, most inhabitants of

the Sudeten Mountains on either side of the border were

Germans. The Czech majority of the country lived in the

Bohemian lowlands. This had not been a problem for the Sudeten

Germans when Bohemia was part of the Austrian Empire. They had

been among the privileged Germans who ran the empire, but now

they were an ethnic minority in a Slavic land. In practice,

the Czech government treated them quite well, just like they

treated anybody else. German was one of several official

languages across the republic, and most districts had a wide

degree of local autonomy.

Even so, Hitler began making noises about the Czech mistreatment of its German minorities. Loud, warlike noises. He refused to let so many Germans live under the thumb of an alien power. Ever since he had come to power, Hitler had rebuilt Germany into a great power again. He expanded the German army, equipped it with all the latest technology and redeployed it along the border with likely enemies. In 1938, Hitler annexed Austria, which put German armies along three sides of Czechoslovakia.

Czechoslovakia couldn’t fight off a full German invasion by itself. Even a couple of powerful allies might not be enough. It had taken the combined might of four great powers (France, Britain, Russia and America) to beat Germany during the First World War, which had been a close contest that Germany had nearly won. With a new war brewing in Europe again, France and Britain alone had little chance of stopping another German outburst without help. The problem was that France and Britain considered Stalin to be just as bad as Hitler, and they weren’t going to ask him for help.

At the Munich Conference in September 1938, France and Britain agreed to give peace one more chance and let Germany have the Sudeten Mountains if that would make Hitler happy. In exchange, Czechoslovakia got to watch. To show the world they were trying to be fair and not just knuckling under to Hitler, the Munich Conference gave other neighboring nations pieces of Czechoslovakia too. Having lost one-third of his country, Czech President Edvard Benes resigned and moved to England where he’d be safe from the inevitable German invasion.

One advantage of a border along the Sudeten Mountains would have been that this made an excellent defensive position. Now that the borderlands were handed to Germany, Czechoslovakia became indefensible. With all their border fortifications inside Germany, the Czech army was neutered without a shot.

In March 1939, prompted by German agents, Slovakia declared its independence and set itself up as another fascist country, leaving Czechia on its own. Hitler then summoned Czech President Emil Hacha to meet him in Berlin right away, where Hacha was told that German troops were about to cross his border to restore order and it would be unwise to put up a fight. The shock gave Hacha an immediate heart attack, but the Germans propped him up and revived him with an injection, keeping him conscious long enough to sign the surrender papers.

With Czechoslovakia in his pocket, Hitler could now attack Poland from three sides, which he did on September 1, 1939. This time, France and Britain declared war. Meanwhile the last spasm of Czech democracy saw student demonstrations that were snuffed out on November 17, 1939, when Nazi troops stormed the University of Prague. They executed some troublemakers immediately, hauled off 1,200 students to concentration camps, and shut down all colleges in Czechoslovakia. Two years later, exiled Czechs students and their friends in England commemorated the anniversary of this event as International Students’ Day. We will see this holiday a couple more times before this book is done.

![[Previous Chapter]](images/previous_arrow.gif) |

![[Next Chapter]](images/next_arrow.gif) |

① Romania had been semi-democratic under the 1923 constitution. The Senate was composed of elder statesmen, retired generals, select royalty, along with elected representatives from universities, the chamber of commerce and other such august bodies. The Assembly of Deputies was elected by direct, secret, universal, compulsory male suffrage. To keep coalition governments to a minimum, he party that won the most votes in the general elections (and at least 40%) automatically got 50% of the seats in parliament, with the rest distributed proportionately.

② Australia formally accepted independence in 1942, New Zealand in 1947. Newfoundland’s independence, on the other hand, didn’t quite work out. It went broke during the Great Depression due to corruption and mismanagement. The prime minister of the dominion had to flee the capitol building one step ahead of an angry mob. Newfoundland reverted to British colonial control in 1934 until it was incorporated into Canada in 1949.

③ Nowadays national leaders usually travel securely by private aircraft or armed motorcades along closed streets, but in an era when trains were the only way to travel quickly overland, leaders had to mingle with everyone else at the station. This was the best place for an assassin to catch them close up. American President James A. Garfield was also assassinated at a train station in 1881.

Ⓐ Graham Darby, “Hitler's rise and Weimar's demise: Graham Darby points to common errors and omissions that should be avoided”, History Review, September 1, 2010

Ⓑ Malcolm Duncan Kennedy, The Estrangement of Great Britain and Japan, 1917-35, Manchester University Press ND, 1969, p.230

Ⓒ Dylan Riley, The

Civic Foundations of Fascism in Europe: Italy, Spain, and

Romania, 1870–1945, JHU Press, 2010

Ⓓ James Eskridge Genova, Colonial Ambivalence, Cultural Authenticity, and the Limitations of Mimicry in French-ruled West Africa, 1914-1956 (Peter Lang, 2004)

Copyright © April 2019 by Matthew White

![Picasso, Guernica [Picasso, Guernica]](images/1937-guernica.jpg)